Arctic ice melt

2012-08-31T01:20:31+10:00

Sea ice is retreating faster than expected, SIMON WEBSTER reports.

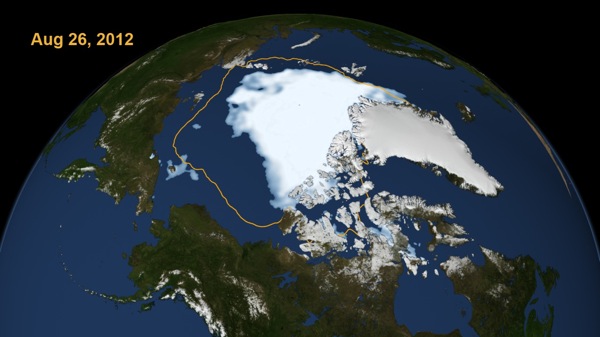

Last Sunday, August 26, while we were all sitting down to our pancakes and coffee and reading the football results and gossip columns, the extent of Arctic sea ice dropped to the lowest level recorded in more than 30 years of satellite measurements.

The new mark beat the record set in September 2007, say scientists from NASA and the US National Snow and Ice Data Centre, and it’s going to get worse: there are still three weeks of ice shrinkage to go as the northern summer peters out.

The orange line in the image above shows the average minimum ice coverage from 1979-2010. It’s normal for Arctic sea ice to shrink during summer: some of the ice is seasonal. But what’s particularly worrying is that this Arctic summer hasn’t even been particularly hot. It’s not just a case of lots of temporary ice melting; the perennial stuff is on the retreat too.

“Unlike 2007, temperatures were not unusually warm in the Arctic this summer,” says Joey Comiso, senior research scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Centre. “The persistent loss of perennial ice cover – ice that survives the melt season – led to this year’s record summertime retreat.”

In other words, according to NSIDC research scientist Walt Meier: “It’s an indication that the Arctic sea ice cover is fundamentally changing.”

This NASA animation shows how the ice retreat works, with the loss of temporary ice leading to the perennial ice thinning and disappearing over time.

It’s all happening a lot quicker than expected. As this sobering column by Guardian columnist George Monbiot points out:

In its last assessment, published in 2007, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change noted that “in some projections, Arctic late-summer sea ice disappears almost entirely by the latter part of the 21st century.” These were the most extreme forecasts in the panel’s range. Some scientists now forecast that the disappearance of Arctic sea ice in late summer could occur in this decade or the next.

Monbiot ends his column by quoting from The Tempest, with the great globe itself dissolving, and he may be right. But rather then end this blog entry with despair, I will instead remind you of the intensely empowering, soothing, inspiring and carbon-friendly qualities of the practice of growing your own food. And I will point you towards the website of the Permaculture Research Institute, firstly because – credit where it’s due – it’s where I found the Monbiot column, and secondly because, while permaculture may not be the panacea that some of its proponents claim, it at least offers some hope, and a course of action.