Going to the big trees

2017-05-15T05:25:47+10:00

Join Dr Resse halter on an expedition to find (and hug) the world's tallest trees.

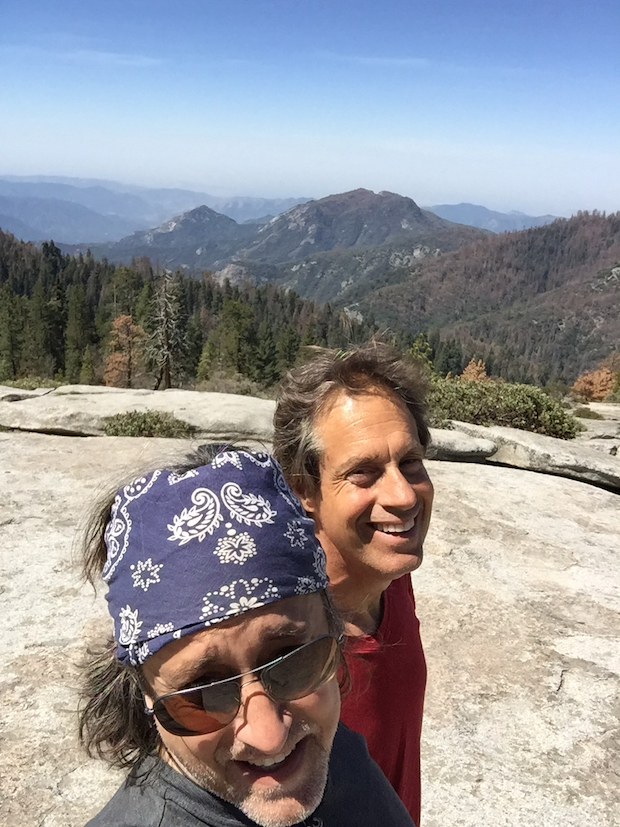

Last week, my brother Jason and I left the City of Angels, an hour before sun up, in search of the largest trees of the face of the Earth: sequoias.

These timeless beauties can easily reach 3000 years of age or the equivalent of witnessing 1,095,750 sunrises. One giant sequoia contains more wood than an entire hectare of an eastern United States hardwood forest.

Around 7am, we reached the southern Sierra Nevada range. We climbed through the only single-needled pines on the globe, the legendary drought tolerant California pinyons and their constant companions California junipers.

As we ascended through the salubrious oak woodlands, the forest type above the pinyon/junipers, the forest canopy began to close because there was more available mountain moisture.

Nature’s well-orchestrated music, splendid rat-atat-atat-tat, the bark beetle-consuming Northern flickers and Pileated woodpeckers greeted us; pure mountain air, gorgeous aromatic cedars and splendid, tall white firs superseded the oak forests.

We stopped at the first waterfall and celebrated the snowpack meltwater, the lifeblood of planet Earth, by quickly dunking under an icy, invigorating shower.

Soon after, we discovered a magnificent 86m tall sugar pine – the tallest of all 111 pine species – with its 350mm long cones, the longest pine cones in the world.

The best was yet to come. Around the next switchback, we glimpsed the first of many colossal sequoias, affectionately known as ‘big trees’. The enormity of these ancient ones is truly mesmerising. Each specimen is nature’s finest living masterpiece.

With the assistance of a panoramic setting on our personal devices, we were able to capture some of these awesome cathedrals. All the while, Douglas squirrels and flycatchers kept about their business, feasting on sequoia seed caches or dining on freshly hatched robber flies.

Onward we forged until we met the regal General Sherman – the largest living tree on Earth – nestled in a pocket that on average receives 6m of accumulated snow, or snowpack, each winter.

At over 83.8m tall, the General possesses an enormous girth at the ground of more than 31.3m. Staggeringly, there is no taper in his stem 55m above the ground, rather it’s a stupendous wall of wood. The General is the King of “the noblest of a noble race”, wrote John Muir, 19th century naturalist and co-founder of the Sierra Club.

After paying homage to the King, we hiked a little higher before encountering a snow-covered forest floor belonging to the sublime Red firs and tenacious Lodgepole pines. At the feet of the elegant firs and genial pines, we immersed our feet in a pristine Sierra meltwater creek. Oh, how glorious.

It was indeed the most spiritual and memorable day that two brothers could wish to share.

Our only regret to report was a 45 per cent death rate of many forests that we examined. The Sierra Nevada forests have been lambasted by rising temperature, prolonged heatwaves, repeated droughts, diminishing snowpacks and bark beetle epidemics – all telltales of the climate in crisis from burning fossil fuels.

The Sierra forests are in need of nature’s ecological broom – wildfire – to reset her biological clock.

Sequoias have evolved around wildfires. Metre-thick reddish bark and crowns that begin 50m above the ground are excellent ecological adaptations to fire, which protect these revered ancient ones. They face, however, a bigger concern, a downward trend in the depth of the overwintering snowpack.

Sequoias require vast amounts of spring meltwater from accumulated snowpacks to contend with a long, hot, dry, fiery Mediterranean-like climate – the only place left on the globe for some 75 sequoia groves along the western range of the Sierra Nevada.

Have you hugged a large tree lately? If not, why not? The time is now!

Dr Reese Halter’s upcoming book is entitled Save Nature Now. Discover more about Dr Halter here.