Why grow heirlooms?

2021-08-23T14:00:01+10:00

Heirloom edibles are important to our survival, and that of the planet. Read on for more reasons why the OG team love growing them.

Heirloom vegetables and heritage fruit have been the backbone of agriculture and home gardens for thousands of years. Ever since our ancestors began collecting wild plants and growing, selecting and improving them to produce bigger, sweeter and more reliable crops, humans have grown, nurtured and cared for these precious plants.

It’s only since the introduction of industrial agriculture, F1 hybrids and the actions of a few of our biggest companies, that these thousands of precious, diverse cultivars of fruit and vegetables have begun disappearing from gardens, farms and seed banks all over the world.

Genetic diversity

Why is this important? As Doctor Judyth McLeod puts it in her excellent Heritage Gardening, ‘It’s about the need to save your future with your heritage from the past’. She goes on to explain that genetic diversity has everything to do with the stability of food production worldwide. We rely on the diversity of our domesticated fruit, vegetables and grains for the very survival of the human race.

Over more than 10,000 years of careful selection by generations of farmers and gardeners, hundreds of thousands of heirloom seeds and heritage fruits were developed. One hundred years ago, most of these were still available, but in the last century, in developed countries, more than 90 per cent of these cultivars have been lost. During the same period, nearly 90 per cent of the heritage apple varieties available worldwide have also disappeared. And there are similar losses for other fruit.

These losses are not recoverable: the gene pool is permanently diminished and with modern agriculture and land clearances we have also lost many of the wild species that originally gave rise to these cultivated varieties.

In 2012, 10 of the world’s top seed companies controlled more than 75 per cent of all global seed sales. Many of these companies are also agricultural chemical companies including Monsanto, Dow, Bayer and Syngenta. At the end of May 2018, the US Justice Department gave approval for the German drug and gene company Bayer to take over chemical and seed company Monsanto. Soon, if other takeovers are approved, there may be just three companies owning most of the world’s seeds.

An essential bounty

I know that to some of you this will feel overly dramatic, but it’s essential that we all realise how close we have come to losing this essential bounty, created by generations of our forebears. We need to keep fighting to maintain what we have left.

Fortunately, there are also good news stories. Communities, grassroots movements and small businesses have been fighting back and although huge numbers of cultivars have been lost, we still have thousands of different cultivars that with a bit of community effort can be preserved. In my own small garden I grow more than 20 different heritage fruit trees, and only ever save, buy or grow heirloom vegies. If we all did the same then this would be a huge step toward preserving what is left.

Heirloom vegetables

There’s a lot of confusion over the names used for the early cultivars of vegetables and fruit trees. So a few definitions might be helpful. In Australia, the most common term for

old vegetable cultivars is heirloom. Some say that vegetable cultivars need to be at least 50 years old before they can be called heirloom, while others claim that there should be a history or story associated with them or that they need to have been passed down through several generations. It’s now much more common, though, for the term ‘heirloom’ to be synonymous with ‘open-pollinated’, meaning that an heirloom vegetable is any non-hybrid from which you can collect seeds and regrow plants that generally grow true to type.

This is the definition used for the Essential Guide: Heirlooms. Recently developed open-pollinated vegetable cultivars are often called modern heirlooms. By growing heirloom vegetables, gardeners and farmers can select their best plants and save seeds from year to year; these seeds are free and owned by everyone.

Heritage fruit trees

In Australia, old fruit-tree cultivars are usually referred to as ‘heritage’. In other parts of the world, heritage is also applied to vegetables, while fruit trees can be known as heirlooms. The first European fruit trees in Australia were probably apples planted by Captain William Bligh on Bruny Island, Van Dieman’s Land before European settlement of NSW. These would be Australia’s first ‘heritage’ fruit trees. (This doesn’t take into consideration Australian native fruit trees that have been eaten and cared for by First Nations people for many thousands of years). Later successive European arrivals brought more fruit trees and by 1857, the Royal Tasmanian Botanic Gardens boasted 111 apple varieties, 54 pears, 25 plums and 8 oranges.

These numbers continued to grow across Australia and were essential for the survival of early settlers. Cultivars suited to Australian conditions were developed and thrived well into the 1900s. They were found in commercial orchards, state agricultural nurseries as well as smaller farms and our gardens. But broad-scale agriculture has meant that only a few cultivars suited to long transport and storage now survive, and many old orchards and agricultural sites have been bulldozed to make way for development or just because there is no-one to look after them any more.

So many heritage fruit trees have also been lost. Fortunately, as with heirloom vegetables, there were also groups of people who realised we were losing our legacy of diversity in fruit trees, and started to preserve old orchards and cultivars. Also some of the legacy of our heritage fruit trees can be found in unusual places. When driving along rural roads in southern temperate Australia you will see old fruit trees including apples, plums, peaches, figs, pears, loquats and chestnuts growing on the road reserves, and in old cemetaries and derelict house sites too. These undervalued trees are sometimes seen as weeds by local councils when, in fact, they should be regarded as cultural and horticultural resources and a treasure trove of diverse fruit DNA. In my 20s I cycled through large tracts of the UK and Ireland. With almost no money, I lived on soya beans soaked during the day in my spare water bottle, and cooked them at night combined with greens collected from roadsides and hedgerows. To add to this very basic fare, I also collected fruit from the diverse heritage fruit trees on roadsides, in parks and remote hedgerows. I never been so fit and healthy!

With the Essential Guide: Heirlooms we hope to introduce you to some of the wealth of heirloom and heritage plants in Australia, and encourage you to grow, save and share them with family, friends and communities.

The future of our food is in our hands.

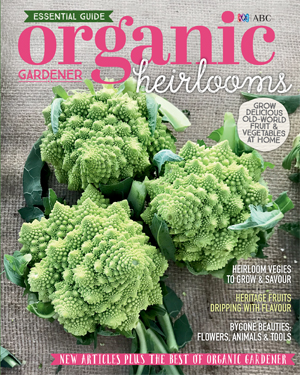

This blog was first published when our guide to growing heirlooms first came out, but you can still get a copy of Organic Gardener Essential Guide: Heirlooms as a digital version.