How to put in place a crop rotation plan

2024-05-22T00:50:44+10:00

A crop rotation plan will help avoid pest and disease build up in your garden.

Gardens are never static. They are dynamic spaces, constantly evolving and changing, usually through natural processes but sometimes through the interventions of the gardener.

This is never more true than in a backyard vegetable garden. Here, in a patch governed mostly by the seasons, garden beds are in state of perpetual change, with soil that is constantly being drawn upon and replenished, diseases that come and go, pest outbreaks that explode and then recede, crops that are sown at the start of the season and pulled at the end.

How crop rotation helps

One of the key methods gardeners can use to break the cycle of pest and soil-borne plant diseases is crop rotation. Basically, not growing the same crops in the same bed year after year. Also, with a bit of planning, this also allows you to best fit different crops with varying nutritional needs into your cycle.

Soil pests and diseases are the main concern and can accumulate in a bed if the same crop is grown repeatedly. An example is fungal wilt disease affecting Solanaceae crops like tomatoes. To break the cycle of reinfection, it’s helpful to not plant tomatoes and their relatives in that bed for at least a couple of growing seasons.

Soil nutritional cycles

Every crop has a particular nutritional need. Cabbages and corn, as examples, are greedy plants in need of rich, well-nourished soil. By contrast, carrots and their relatives are scavengers. They can make-do with lean soil, as long as it’s loose and friable. In crop rotation terms, it’s a good idea to plant carrots after a crop of brassicas in the same garden bed. The brassicas will have gobbled up most of the nutrients, leaving slightly deprived soil favoured by sweet and chunky root vegetables.

Flip this script with legumes. Crops such as broad beans and peas fix atmospheric nitrogen in the soil via nodules on their roots. They enrich the soil. Once they’ve finished cropping, you can cut the plants off at ground level, leaving the root system in place to help feed a subsequent crop that likes greater nutrition.

A crop rotation plan

This rotational process is straightforward when you’re talking in terms of two crops, but to devise a rotation plan for a garden with multiple beds and dozens of different crops can become something of a puzzle.

I try to keep things very simple in my garden, so I use a basic system that I call LBR. It stands for legume-brassica-root. I start with a fresh map of my garden beds each season. To each bed I allocate one of the LBR crops. Next season, I move each of the LBR crops to a neighbouring bed. This way, each bed gets roughly a year’s break from growing a

crop from the same family.

What about sweet corn, lettuces and onions and all the others that aren’t my LBR crops? I allocate space for them among the main rotational crops. Sometimes they’ll share a bed, sometimes they’ll have a bed to themselves and will slot between one of the LBR’s.

Once you get to know your garden and work with the crops it all becomes second nature. You can even go further and devise a more complex 4–6 bed rotational plan (see below).

Conversely, if even the LBR thing sounds a bit much, let me offer this: ignore it and just move your crops around without much of a plan. The key, as stated in my opening sentence, is that gardens are not static. Move and flow with them and nature

will do a fair chunk of the work for you.

A six bed plan and planting notes

There is no hard and fast way of doing crop rotation. However, plants in the same family, share similar characteristics as well as disease and pest problems, which means they can be grouped together.

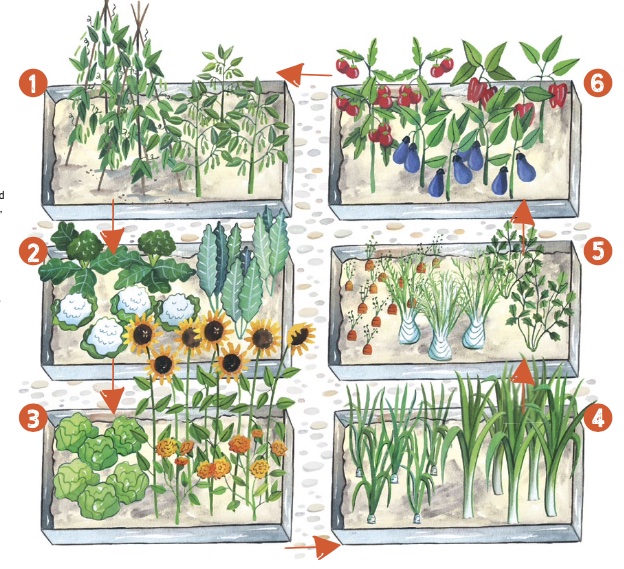

This rotational plan below is based on plant families and is designed to minimise the spread of pests and diseases for commonly grown vegetables and herbs.

It also takes into account some of the nutrient needs mentioned in the Justin’s article (above). If you have less space, you can limit it to fewer family groups, such as 1, 2, 4 and 6, or just go with the LBR system outlined. It’s also a good idea to grow a green manure crop in each bed from time to time (such as buckwheat or lablab in warm season or oats in cool)– simply slash down and leave on surface or dig in. Meanwhile, regular watering with dilute seaweed and worm tea or compost will help keep plants strong and soil healthy, which will prevent many problems occurring in the first place.

1. Fabaceae

This family includes French/runner/lima/soy and broad beans. Also peas and chickpeas. Make sure there is good organic matter in the bed before sowing (compost, well-rotted manure, worm castings) and add pelletised organic high-nitrogen fertiliser after sowing.

2. Brassicaceae

This family includes broccoli, cabbage, cauliflower, kale, Brussels sprouts, collards, turnips and mustards. Leafy vegetables like brassicas need high nitrogen so will benefit from leftover fertiliser in the soil and the nitrogen fixing ability of beans and peas. A later watering with liquid fertiliser will help keep plants growing well.

3. Asteraceae

This family includes lettuce, chicory, endive, sunflower, chamomile and calendula. Asteraceae generally have lower nitrogen and fertiliser needs apart from some liquid fertiliser once growing strongly. Consider planting sunflowers and calendula to the western side to provide shade for lettuces from hot afternoon sun.

4. Amaryllidaceae (specifically alliums)

This family includes garlic, leeks, shallots, chives, traditional bulb onions, plus spring and tree onions. Alliums don’t like nitrogen to be initially too high. Add more organic matter, and just a light sprinkle of blood and bone after planting. Water later with liquid fertiliser and seaweed to enhance bulb swell for onions and garlic.

5. Apiaceae

This family includes carrots, parsnips, Hamburg parsley, coriander, dill, fennel, cumin, caraway and parsley. These plants don’t like too much nitrogen, so don’t add more, but do add some potassium. Banana skins soaked in water for two weeks, with the water poured over the bed, provides good potassium.

6. Solanaceae

This family includes tomato, capsicum, eggplant, potato. These plants have initial low nitrogen needs, but will need extra fertiliser once fruit starts to set, either pelletised complete organic, blood and bone, or complete liquid fertiliser.