In conversation with…

2018-06-27T01:27:01+10:00

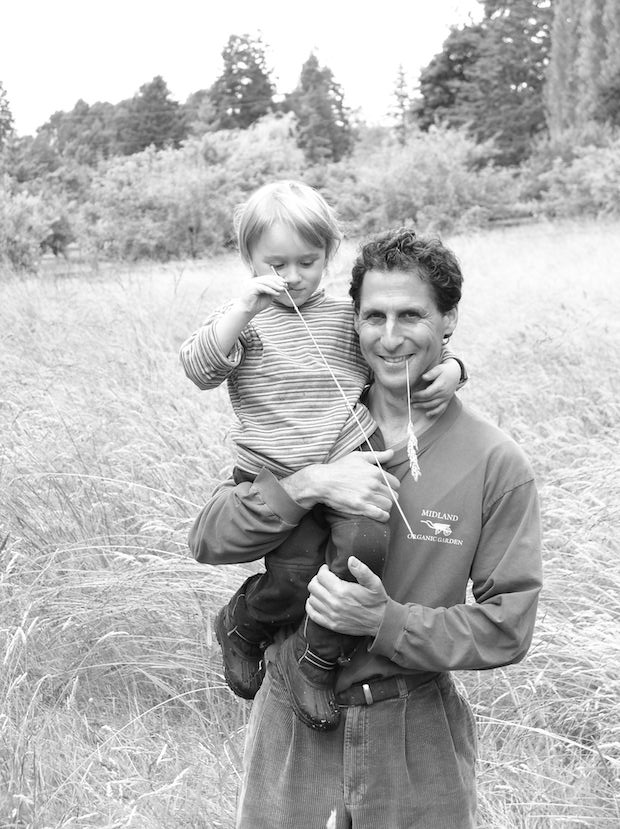

Simon Webster chats with organic farmer and author Michael Ableman about the healing power of growing food.

Q: What was the best thing to come out of the Sole Food Street Farms [an urban farm created in the slums of Vancouver, Canada] project?

A: There were two mandates. One was an agricultural mandate – to create a credible model of urban agriculture. I started the Centre for Urban Agriculture in California in the early 1980s, but still after all those years I felt I hadn’t really demonstrated there was the possibility of a full-scale production model in the city.

Sole Food produces 25 tonnes of food annually on five acres. The scale we’re working on is amazing and people would say it has been a success agriculturally. But for me, the biggest success has been social. Sole Food employs 25 people with various issues, mostly around drug addiction and mental illness. We have individuals who came to us as hard-core crack addicts who are now functioning, productive, highly skilled farmers, and that’s really satisfying, probably more than anything else.

Q: What role do you think urban farming and small-scale farming can play in Western industrialised societies?

A: I feel small-scale farming is going to more and more be the dominant model. It’s fairly well documented that the smaller the acreage, the more productive it can be, the better the quality of that production and the more vitally the soils can be maintained. It comes down to more hands and eyes per acre. Small-scale farms are also well positioned to thrive as climate change plays out. They’re more adaptable and may be able to navigate through these changes better than large farms. As for urban farms, there is great opportunity for economic enterprise growing food in our cities. That said, I don’t have any romantic notion that our cities can feed themselves. The conversation we need to have is about where urban farms fit in with our broader food system – what’s appropriate to grow where, and in what quantities.

Q: Organic Gardener visited your 120-acre Foxglove Farm back in 2009. What’s changed on the farm since then?

A: We’ve gone through a simplification process. What are the things we do really well and are unique? What’s our niche in the market? What do we grow that will create the most successful fertility cycle for the land? And what will help us sustain ourselves?

I’m 63, and in great shape, but most of us at this stage of our lives look forward and say, what’s the transition, who’s next, and how do we make opportunities for a younger farmer to take over? Most of my colleagues are having this conversation. I’ve been quoted as saying, if you want your kids to farm, don’t raise them on one, and there’s some truth to it.

When you’re younger it’s OK if you work yourself like crazy. As you get older you think let’s be smarter, let’s narrow the crop mix to things that are going to work for the land, work for the marketplace and work for us.

Q: How has the organic farming movement changed since you started out in the 1970s?

A: I’ve seen the industrialisation of organics in the [United] States. I’ve seen big changes in what is acceptable in terms of organic production and a whole range of levels of commitment to the basic tenets of organic.

It has been a watering down of the movement. But there is a contingent of individuals who have held strong.We have an obligation to revisit what we’re doing, and to challenge ourselves to continually push the edge. Those of us who have been doing this a while have developed some skills, but we have some questions to ask ourselves. What is our role as we witness climate change? How can we apply our knowledge to help navigate climate change and nurture and teach new farmers?

[Fellow organic pioneer] Elliot Coleman and I formed an organisation a few years back called Agrarian Elders and these are some of the ideas we’re tackling.

Q: How do you think our food culture is going to change in the coming decades?

A: I think people will become more connected to their food. Climate change may require a decentralisation of food production. It may be better that farmers focus on the engine of the diet – pulses, grains, dairy and meat – while individuals and families and neighbourhoods grow fruit and vegetables. People will need to become more involved. In many ways it will be a positive shift.

Q: How did the Sole Food project affect you personally, and your hopes for the future?

A: In many ways I have been as much a beneficiary of this project as the people we were trying to help. My attitudes have completely changed about addiction and I have new respect for people who deal with that. It’s one of the biggest burdens anyone can carry.

If those folks can lift themselves out of bed each day when they’re dealing with major demons, there’s no question that the rest of us have that potential as well.